sm

smSECTION THREE

sm

sm

COLUMN THIRTY-EIGHT, OCTOBER 1, 1998

(Copyright © 1998 Al Aronowitz)

THE CRUCIFIXION OF REINALDO ARENAS

BY MANUEL MENÉNDEZ

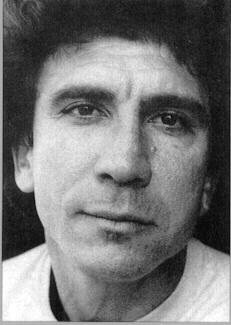

REINALDO ARENAS

(Photo copyright (c) Marcia Morgado from back cover of

Recuerdo y Presencia [Edición de Reinaldo Sánchez])

He was gay, he was a talented writer, he was a dissident. He had on him all the elements of an enemy, and therefore had to be destroyed. And what Castro's carcelary system couldn't achieve, the exile completed: he contracted AIDS, and after three years battling it, he decided that life at that price was not worthwhile. He killed himself in December 1991, on Christmas Day. In a seedy hotel room in Manhattan. By an overdose of "Mogadon." He was 47 at the time.

And he was the most talented Cuban writer of my generation, those born on the '40s, too young to have known freedom, but old enough to suffer the brunt of Fidel Castro's dictatorship. We who had no youth.

Reinaldo left behind seven novels translated to five languages; a book of short stories; another of poetry: Leprosorium; another of essays: The Quest for Freedom, and three theater pieces. But the 11 million Cubans in the Island have no access to his work: Arenas has never been published in his own country. Sad, but he is better known in France than in Cuba.

His early childhood seems like a Faulkner story. Growing up alone, a true child of Nature,

His grandmother, who peed standing and talked to God, ruled the household of 17

running naked and barefoot amid the trees. Meningitis, cured with herbs and water sprinkling by a Holly Roller. Intestinal worms. Lost there in the middle of nowhere: seven miles from Gibara---the very sticks. A huge bohío, built of palm logs and fronds, battened earth floor, no sanitation, a well that dried in summer. Just like in the times of the Cuban Indians. His grandmother, who peed standing and talked to God, ruled the household of 17, which included her own eleven daughters---most deserted by common law husbands---and the true cross of her life: her own spouse, impenitent drunk, womanizer and wife-beater, and worse, a vociferous atheist.

Who all lived off the land, barely so: seven acres of stony, gray, depleted earth. Maize; some plantains, cassava, yam, sweet potato. Slaughtered one or two pigs a year. For Christmas. A couple dozen scrawny chickens. Montunos. Dirt poor.

The grandmother was illiterate, but all her offspring went through primary school. Or else. She sent every one of them to the Escuela Pública, all six grades under a benign, angelic lady teacher, three miles away, no matter the weather, on a horse or a mule.

Reinaldo discovered, or rather intuited, his own homosexuality when he was six. It was San Juan's day, and the young men from all nearby hamlets assembled beside the river, and naked, splendid, dived from a huge rock---a meteorite---strong, supple, and those first seen water dripping genitals would haunt him for the rest of his life.

For many years to come he would be ashamed of being a cundango, as they say in Oriente. Rejecting his "sexual weakness." Awareness exacerbated by the promiscuity of the overcrowded intern school, a former Batista barracks. Studying to be a Koljós manager. All those country boys naked in the shower stalls. Trying to drown his desire by hitting the books. Mathematics, Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist texts. Critic of Sane Reason.

By then his family had sold the land and settled in Holguin, in an old house whose front room served as grandfather's store: sold fruits and vegetables. It was a Saturday evening, and Reinaldo had ahead five days of leave. He was happy. Then it happened, at night, the inevitable so awaited. A young swarthy stranger, Raúl, gripped Reinaldo's penis in the darkness of the back seat of a Gypsy taxi-cab going back to Holguín.

There were then three hotels in the plain, drab, hick town, and the employees didn't frown yet upon two men renting a single room. Reinaldo always the passive, Raúl the "man." They would be lovers for the next two years. He would abandon Reinaldo without explanation. Without a farewell. Waiting for weeks in vain. Blackness.

By then things starting going tougher for the queers in Cuba. Raúl Castro, a queen himself, started persecuting the homosexuals. They had to be "rehabilitated," converted into men. Or perhaps he wanted to rehabilitate himself, to forgot his Jesuitical, adolescent mariconería, his long romance with Rolando Cubelas. In 1963 Raúl Castro established the first concentration camps for his fellow gays, the infamous UMAPs, which went on crushing lives and talent for seven years.

At the time Reinaldo was mismanaging a chicken farm. Giving orders to disgruntled peasants whose lands had been expropriated. And was barely holding on to sanity. Anguished, bored stiff by that meaningless life in Oriente's countryside, writing poems on the battered, faithful Underwood.

Miracles would happen twice on Reinaldo's life. The first one took place on the summer of 1967. Castro the Júpiter Olímpico summoned Koljós managers from all over the island to Havana, for his yearly 26th of July speech at the Plaza de la Revolución, apex of his paranoia.

Had lodged all those "agricultural administrators" in the Habana Libre, formerly the Hilton. Guajiros taking craps in the bidets, wrecking the TVs and air conditioners. Convoked all to the former casino hall, and there The Maximum Leader appeared to them still hallucinating, grandiose, fishbelly pale flesh showing through the olive green shirt. Going flabby already. Greasy beard.

And He told them, among other foam from the mouth, that those who passed an examination would go straight into Havana University's School of Economics. Few did; Reinaldo crammed and was one of the chosen. Stayed in Havana. Fulfilled wanderlust. Soon quit University and went to work as a clerk at the National Library. Reading day and night every free moment, covering in a week as much literary terrain as in an academic semester. Not chaste, but careful, with Miguel Barnet, a then important official writer.

Reinaldo became a dissident precisely during another of Castro's speeches, this one on the steps of the former American Embassy. Claiming that the CIA had kidnapped some Cuban fishermen in a Caribbean island that happened to be British. All so phony, so obviously staged. After beating about the bush for three hours, Castro told the Cuban people that there won't be after all a "10-Million-Ton Sugar Harvest." The economy wrecked, and all that effort and sacrifice wasted, Reinaldo's included, just back from cutting cane for almost a year in Pinar del Río province. "Voluntary like the Chinaman"---as they say in Cuba.

Like the flash on the road to Sodom, the anagnorisis, Reinaldo realized that the ranting tyrant was lying through his rotten teeth, that he had been cheated of the best part of his youth, and then and there shed for good the mask of fictional hombría. And swore to throw instead ten million palos. [In his autobiography, he reckons he had had sex---mostly in the passive role---with 500 men and a dozen women.]

That August 1970, and for ten days, a frenzied Saturnalia went on in Havana. After two years of Prohibition, alcohol flooded the city, a cornucopia of beer and rum. The belated Carnival was taking place, and on the floats parading along the Malecón, the splendid and drunk dancers threw away their sequined bikinis into the cheering crowd, and danced naked.

The People fucked everywhere. The lucky ones at home or at a posada, the less fortunate or those come from the provinces, under every dark arcade, on staircases, on the lawns of the parks. The underground maricónes had a field day in the wooden urinariums erected along the Malecón. Sometimes the cops would push and topple one of the hut-like structures, to reveal perhaps twenty men, oblivious, drunk and sucking and fucking one another.

From then on, an even darker pall fell over the

island. To be gay in that Stalinist and utterly macho society during the '70s

required a lot of everyday courage. Compulsive writer by now, Reinaldo won for

two years in a row the National Novel Award. Landed a small job at the UNEAC,

the official writer's union, correcting galley proofs for an insignificant

monthly,

His other obsession by then was diving. With goggles, snorkel and flippers sent over by Spanish friends, things impossible to get in Cuba. He explored for hours on end Havana's underwater reefs.

And every night, dodging the vigilance of his aunt, a self-proclaimed informant of the State Security, he would entertain in his room six or seven lovers: 17-year-old Army recruits, and apprentice athletes from the INDER School next door. All those kids naked and rampant, possessing him, awaiting their turn, some of them repeating, exacting from Reinaldo orgasm after orgasm. Sometimes even the teachers and the Young Communists would come, too, to their mutual embarrassment.

Reinaldo Arenas' literary work is centered on homosexuality, spiced by danger, in a

Reinaldo

was charged with

'Corruption of Minors'

dictatorial society where to be maricón or tortillera was---still is---like being a Christian under Tiberius: thrown to the lions if caught. And the sexual traps were there everywhere, irresistible, lying like land mines. He and another maricón, Coco Sal, sucked two adolescent pricks too many in Guanabo beach, under the uva caleta trees. The six-feet-tall, sturdy teenagers mugged them and to boot denounced them to the police. Reinaldo was charged with "Corruption of Minors."

A good start for the State Security, which had taken an interest on him lately. Ubiquitous, Omniscient, Secret, Pervasive, Feared. Cuba's KGB. He had published abroad his first two novels, Singing from the Well and Hallucinations. First in French translation, and had received remarkable reviews in the Paris press. The Spanish originals, and English and German translations, were about to follow.

That in itself, publishing abroad without State approval, was a crime of lèse majesté. To compound the offense, books with homosexual plots. The same crime committed by Lezama Lima and Virgilio Piñera, the two greatest Cuban writers ever, both acknowledged gays, who would die in obscurity and ostracism, downtrodden by Castro's heavy boot.

By then The Maximum Leader was losing patience with Cuban intellectuals, even those who were under the official fold. He selected as scapegoat Heberto Padilla, a well traveled, drunken poet who took Prague's Spring too seriously. He had won the National Poetry Award in 1968 with a controversial book, Fuera de Juego. Padilla would be sequestered and brainwashed for four months by the State Security. He disgraced himself by an Autocrítica, a Public Confession, in front of all Cuban fellow official writers, who also competed abjectly in laying bare their own sores, their "ideological diversionism."

Reinaldo would suffer worse persecution than any of them. While held at Guanabacoa's police station for fellating willing teenagers, he managed to escape. A veritable manhunt followed. Reinaldo was described in the police flyers as a "CIA agent who raped and killed a 60-year-old woman and her granddaughter." He hid and survived for three months at "Lenin Park," a hunting and fishing preserve and open air zoo at the South of Havana, devised by Celia Sanchez, Castro's secretary and lover in the Sierra Maestro, later santera and voracious tortillera. Reinaldo survived on the meager food the Bronte Sisters---as he called his friends the Abreu Brothers---dared to bring him. And some books he read over and over again. The Iliad, The Magic Mountain.

One day Alicia Alonso was dancing Giselle in the "Lenin Park" Auditorium. The temptation was too great. Reinaldo got caught at the pas de deux by a plainclothes cop that pointed his Makarov pistol at Reinaldo's head, all the time rejoicing: "I won a promotion! I'll make Sergeant!"

Reinaldo was led to the worst prison in all Havana: "El Morro" Castle. Spanish fortress from the 16th Century, totally unfit for human habitation. There were five galeras, or wards, one of top of the other. Number One and Two, the lowest, housed las locas, los maricónes. At high tide the sea would wash through the rusty bars, flooding the wards. To defecate you had to wallow through a mire of excrement. But the maricónes kept their optimism. They stitched themselves women's garments from the bedsheets, wore mascara of white chalk and black shoe polish, and stumbled on makeshift high heels.

Once in a while carcelary monotony broken by a duel with entizados between two locas, at lunch time, up there in the worn stone paved terrace that overlooked Havana at the other side of the bay. Broom handles filled with Russian razor blades. The purpose was not to kill but to cut your opponent's face. The screws just watched and jeered. All wearing sun glasses, showing during bath time, eyeing the parade of naked cons who soaped themselves and waited for the second bucket of water. Sometimes the screws would force a young, good looking con to spread his buttocks.

Suicides, spectacular, performed in the free breeze and the burning midday sun, escaping this time for good the dank, damp, dark wards. Once a black queer suddenly produced a shank, and slashed his own throat, blood spurting like a gush. Senseless murders like that of "Cecilia Vald's," nom de guerre of a "loca" who had a pure, diaphanous but powerful voice that many a professional soprano would have envied. And an envious maricón, a lifer with nothing to lose, stabbed Cecilia 16 times while he slept.

After having a good taste of carcelary life, Reinaldo Arenas was sent to Villa Marista, the see of the Cuban State Security, in the outskirts of Havana. After three months of psychological torture, kept in a claustrophobic cell, he signed a confession acknowledging

A machine-gun burst

passed inches away

from Reinaldo's head

all his crimes. In all, Reinaldo spent two years in prison, the second one in an "open brigade," building apartment blocks for the Russian technicians.

Afterwards a refuse of society. He tried to leave the island on two inner tires. The raft started to deflate three miles from shore, and Reinaldo had to swim back. Strange like him, a peasant, took to the sea. Later, he tried to escape swimming to the American Navy base at Guantanamo Bay. Found himself caught into an impassable Cuban version of the Berlin Wall: concertina wire, land mines, infrared devices that triggered a machine-gun. The burst passed inches away from Reinaldo's head. He climbed a tree and hid there for two days, while the search went on by Border Guards with Kalashnikovs, some accompanied by sniffing German Shepherds on leash.

Then a long interregnum of four years laying low. Apparently tamed, but writing for the third time his novel Once Again The Sea, about a love triangle between a newlywed couple and a youth next door at the beach, and an unsolved murder. The first two manuscripts had been lost in bizarre circumstances. There were no photocopiers in Cuba, not even carbon copy paper, so he had to start again from scratch, reconstructing the book from memory.

Fresh from prison, with his internal passport blackballed, he was unemployable, untouchable, a social leper, under constant surveillance. He subsisted selling five-gallon tins of water, which he pushed all around Old Havana in a wooden cart. The first months of "freedom" without even a ration card, living on boiled eggs and Russian tea. Occasionally, whenever one of his friends succeeded in renting a house at Guanabo Beach, he'll escape briefly from the asphyxiating oppression that the city he had loved before now represented. There they would read aloud their work, and that of foreign banned writers. And waiting outside, the Gulf Stream to go under drunk on cheap rum and tropical sun.

Reinaldo was living in a tiny room in the former "Monserrate Hotel," now a squalid warren inhabited precariously by the damned: maricónes always afraid of being arrested, hookers, petty criminals, marihuana pushers. And the CDRs, the snitches, always nosing and prying on the neighbors affairs. Denouncing you to get your small room.

However, there Reinaldo found for the first time true love, tinged by deep compassion: Lazaro Gómez Carriles, young schizophrenic who wanted to be a poet. Lazaro would share, true till the very end, Reinaldo's last years in the throes of AIDS. He would also become the main character of Arenas' novel The Janitor, the first he wrote in exile.

The second miracle in Reinaldo's brief life was the Mariel Exodus, in July-August 1980, when 130,000 Cubans found their way to Miami. Among them the dregs of Castro's prisons: 14,000 violent criminals and criminally insane. And the gays, of course, hatred still unabated.

Reinaldo's first taste of freedom was bitter. The 90 per cent White Cuban emigrée community wouldn't touch him with a ten-foot pole. To them he was in the first place a Mulatto, then a faggot; and if he were a writer, who cared? The same barriers as in Cuba, but now this side of the sea. Yes: Recognition in Europe. But nobody is prophet in his own backyard. And Miami's doors were closed on his face by the professional patriots.

So he went further North, to New York. The same day he arrived in Manhattan, he and several friends were celebrating at a gay bar on 7th Avenue. Suddenly it began raining like the deluge, and Reinaldo, leaving his coat behind, went dancing through the streets singing at full voice: "Iiiimmm danciiing in the raaiiin. . ." And that's the way I want to remember him.

So full of life. Undaunted. Invulnerable. His last painfully written pages contain no regret, nostalgia or desperation. They are instead a chant to life, to love, and to freedom, political as well as sexual. As he would say in an interview in the French TV, already ravaged by the disease: "I believe that pleasure knows no sin, and that sex has nothing to do with morals. . . "

A year later, he would finish his suicide note with these phrases: "To the Cuban people, in the Island and in exile, I urge to go on fighting for freedom. My message is not one of defeat, but one of resistance and hope. Cuba will be free someday. I am free now." ##

CLICK HERE TO GET TO INDEX OF COLUMN THIRTY-EIGHT

CLICK HERE TO GET TO INDEX

OF COLUMNS

The

Blacklisted Journalist can be contacted at P.O.Box 964, Elizabeth, NJ 07208-0964

The Blacklisted Journalist's E-Mail Address:

info@blacklistedjournalist.com

![]()

THE

BLACKLISTED JOURNALIST IS A SERVICE MARK OF AL ARONOWITZ