sm

smCOLUMN SIXTY-TWO, AUGUST 1, 2001

(Copyright © 2001 The Blacklisted Journalist)

SECTION ONE

sm

sm

COLUMN

SIXTY-TWO, AUGUST 1, 2001

(Copyright © 2001 The Blacklisted Journalist)

STARING DOWN DEATH?

GEORGE

HARRISON AND ME

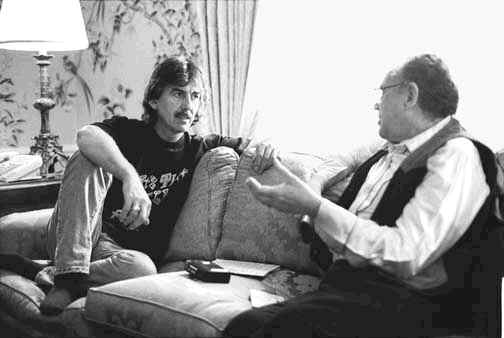

GEORGE HARRISON AND THE BLACKLISTED JOURNALIST

(Photo by Myles Aronowitz)

At

first, I wanted to congratulate George Harrison and me, too, for almost

simultaneously looking The Grim Reaper in the face and then staring down the

ugly motherfucker. We just weren't ready to trip off with Papa Death, not yet,

anyway. That was my belief.

At

first, I thought that maybe I have a mystical partnership with George.

Of course, I suspected that partnership was probably only in my own head.

Doesn't every Beatles fan around the world feel a mystical relationship with

George? Or with Paul? Or with Ringo? Or even still with John's ghost or

spirit? But no other Beatles fan has experienced the history that both George

and I have shared.

From

the time I met him as a Saturday Evening Post journalist covering the

arrival of the Beatles in America to most recently when he sent me to a

chiropractor and to a teacher of transcendental meditation, I have felt my

mystical relationship with him.

I

had never liked alcohol but the Beatles were drinking Scotch and Coke, and so I

began to drink Scotch and Coke. Peer

pressure? When there was no Coke, I just drank Scotch.

But, as I said, I had never liked alcohol and so I arranged to turn the

Beatles on to marijuana.

It

was years later that George sent me to the chiropractor and to the

transcendental meditation teacher. Actually,

that wasn't too long ago during a time of one of the avalanche of crises that

have bedeviled my life. Obviously, I have felt a mystical relationship with

George since then, too.

I

forget how many years have passed since George sent me to that meditation

teacher. She had a sweetness and an

other-worldly spirituality I'd found in all believers in the Maharishi Mahesh

Yogi, that giggling little Indian guru who leads the transcendental meditation

movement. But the Maharishi promised "heaven on earth," and I told George I

couldn't possibly surrender my consciousness to a multimillionaire Indian

fakir who promised heaven on earth. It was my belief that no living being on

earth could deliver on that promise.

'the

Maharishi is nothing but a fake!" Allen Ginsberg had told me.

I'd learned never to take Allen's word as the ultimate judgment, but

I valued his opinions. Fake or not, the Maharishi prescribed two meditations a

day. I didn't have time for two,

so I did my meditation in the morning. I

still do. At first, I held out hope

that the meditation would lower my blood pressure. But even after my heart

attack I continued repeating my morning mantra until I'd drop off into deep

thought. I've found that my

morning meditation helps me prepare myself for my day.

Naturally, I always think of George each morning as I start repeating my

mantra.

George

has made my difficult life more bearable in material as well as in spiritual

ways. With our three young

children, my wife and I were living in a cockroach-infested Manhattan tenement

at the start of her five-year battle against cancer. But George enabled her to

live out her life in rented suburban comfort by giving me a loan of $50,000 that

he knew I could never possibly repay. Was that a sort of tribute to his own

mother's losing struggle against cancer?

George's mother, Louise, died of cancer in 1970. To me, George's

$50,000 "loan? was an exhibition of saintliness unequalled by any rock

superstar I knew.

When

George got the idea for his Concert for Bangla Desh, he wanted Bob Dylan

to participate. Because I had always been the guy who set up the

get-togethers for Bob and the Beatles, George flew me out to the house he was

renting in California and asked me to rope Bob in.

That was easy. Since I introduced them, Bob'd been as much of a fan of

George as George'd been of Bob. And so Bob ended up one of the many headliners

at the concert.

Also

at George's rented house was George's father, Harry, a one-time bus driver.

Harry and I had become buddies during my trips to Friar Park and he was

curious to see what Las Vegas was all about.

So, I took him to Vegas. George's

wife, Pattie, came along with us, too. Once there, I must've made an ass out

of myself, getting drunk and knocking over someone's glass at the roulette

table. I'd never liked alcohol but I won a bunch of money.

At Leon Russell's suggestion, George even sent me to interview Buckminster Fuller to ask for ideas on how to best spend the proceeds of The Concert for Bangla Desh to benefit Bangla Desh's victims. Explaining how human excrement can be recycled into methane gas for cooking, Bucky advocated building geodesic domes to house the Bangla Desh homeless. The concert, however, didn't raise enough money to follow through on Fuller's idea.

George

has always treated me royally. Shortly after The Concert for Bangla Desh, George

released his album, All Things Must Pass.

He called me up and told me he was giving me one-sixteenth of one of

the cuts on the Apple Jam side. Until the CD version was released---Apple

Jam is not included on the CD---people would notice my name among the

credited musicians and ask:

"What

instrument did you play??

'typewriter,?

I'd reply.

Twice

each year since then, I've been receiving royalty checks, however small, from

Harrisongs, George's publishing company.

To a deadbeat like me, those checks have come in handy at just the right

times.

George

and I sat in adjacent seats on the plane ride back to New York from Hollywood

and I think that was another occasion when death was staring at us.

The plane ran into a violent thunderstorm as we approached the city,

tossing the craft around like a rowboat on the ocean during The Perfect

Storm.

"Hari

Krishna, Hari Krishna, Hari Krishna?, George kept chanting as

thunderbolts exploded all around the jet like ack-ack fire.

That

was when George told me he wanted a family, but couldn't because of a problem.

It was when he married his second and current wife, Olivia, that the problem got

solved. His son, Dhani, is now 23.

Although

Eric Clapton was often at Friar Park to jam with George the times I was

George's guest there, I obviously was too thick to notice the budding romance

between Eric and Pattie, then still married to George. Back then, George had

another buddy who was always at Friar Park when I visited---Terry, an auto

salesman. There was one night when

George surprised me by stealing away to his bedroom with the woman I thought was

Terry's girl friend. Did I tell

you I was thick? She wasn't

Terry's squeeze at all. Terry, it

turned out, was gay.

Once

I was there when Yoko Ono showed up. This

was during that lull in her marriage when she sent John off to tryst with May

Pang. As I recall, Yoko spent an entire day at Friar Park lamenting to George

and to Pattie about how much she missed John.

On another one of my visits to Friar Park, I took along my dying wife and

our younger son, Joel, then 11. What

Joel still remembers about the sprawling estate is that what impressed him the

most was the gatehouse. We passed the gatehouse as we drove into the grounds.

We were living in a rented house in mansion-studded Englewood, N.J., at

the time and as we entered the estate, Joel blurted out:

"My

God! The gatehouse is bigger than any of the mansions they have in Englewood!"

With

its stone gatehouse, Friar Park was designed and built according to the whimsy

of a fabled old British millionaire named Sir Frankie Crisp, who apparently

pictured himself as some sort of Peter Pan and whose ghost is said to still

haunt the place. However, in all my

visits there, I never bumped into Sir Frankie. The entire grounds were designed

as something of a theme park, a place to delight a kid of any age. With his own

fascination for roly-poly brothers of the church, Sir Frankie put a friar's

face on every one of the doorknobs in the 120 rooms of his castle.

By the last time I visited Friar Park, George still hadn't completed

furnishing all the rooms.

With

his usual graciousness, George proudly showed off the place to Joel, taking him

on a tour that started with the topiary, a zoo of animals sculpted from bushes

or hedges. There were also a couple

of small lakes equipped with rowboats in which you could paddle through

underground caverns and even through a 'skeleton? cave to a miniature Isle

of Capri. Like every castle, Friar Park has a turret.

On one visit to Friar Park, I brought a pennant for George to run up the

turret flagpole, but I don't know if he ever did.

Exhibiting my typical arrogance, the pennant proclaimed: "Al Aronowitz

Is Here!"

Mostly,

I recall a "Dark Horse? pennant flying from the turret flagpole. "Dark

Horse? was the name of George's record label, based in California, where he

discovered his present wife, Olivia, Dhani's mother. She worked, as I recall,

as a secretary at Dark Horse, but I remembered George couldn't stop talking

about her after he met her.

Scattered

with stone-carved gnomes and gargoyles and with meticulously manicured gardens,

Friar Park also boasts a greenhouse, in which George has found another

passion---gardening. One commentator has written: "It's not unusual for George

to be hip-deep in fertilizer tending to his beloved gardens." When I last

phoned to talk to him, that's where he was.

In his garden.

In

fact, George sent me flowers when he heard I was in the hospital, first for my

heart operation and then again for an attack of phlebitis in my right leg.

Phlebitis occurs from a blood clot in the leg that makes the leg swell up

almost to the size of a small tree trunk. My

problem is that I'm too prone to blood clots.

Yes, George has proved a better friend to me than I have been to him.

We

used to have great times together when George'd come to New York, mostly

accompanied by Beatles No. 2 road manager, Mal Evans but sometimes accompanied

by No. 1 road manager Neil Aspinall, now managing director of Apple. Neil

eventually became my best friend. Mal

was a buddy, too, and, with George and Mal or Neil, the three of us would

usually dine at David's Pot Belly Restaurant in the Village, which featured a

cuisine specializing in all kinds of exotic omelets, something suitable for

George's vegetarian palate. I?d

become acquainted with David and his delectable omelets when he'd been the

caterer backstage at the Woodstock Festival. His restaurant wasn't far from

Sheridan Square.

Which

was where George decided one night that he'd like to take a ride on a New York

City subway. He was dressed in his denims and wore a longish beard. Still, he

looked like nobody else. We descended the Sheridan Square subway steps, bought

our tokens and waited patiently on the platform. We got on the next uptown train

with only a few other passengers in the car.

Immediately,

George drew stares on our trip as the train headed uptown.

Otherwise the trip was largely uneventful until we exited the train one

stop to the North at 14th Street. At that very moment, a gang of cops

with drawn guns was chasing someone up the platform.

I think that was George's first and last ride on a New York City

subway.

There

was also one Thanksgiving when my dying wife insisted on inviting George and

Pattie to share a turkey dinner with us. We were living in the house in

Englewood that George's $50,000 loan had enabled us to rent.

My dying wife, who at that time had to wear a neck brace, was then living

on a diet of pain-killers that would get her so stoned she would sometimes fall

asleep at dinner with her face down in her plate.

Although both George and Pattie were vegetarians, they graciously ate the

turkey my wife had so arduously prepared.

I

wrote many stories

about George visiting

New York

I

wrote many stories describing George's visits to New York, some of them for my

POP SCENE column in the New York Post. I'm going to include one here

that I can't recall ever having been published.

The executive editor often maliciously killed columns I wrote for no good

reason. This column was written

when the Beatles were breaking up:

Sunrise doesn't last all morning

The cloudburst doesn't last all day

Seems my love is up and has left with no warning

But it's not

always gonna be this gray*

Come walk with George

Harrison in New York's parade, brightening the city's sidewalks as he leaves a

trail of double takes behind him, a long-bearded figure in faded denim while

the sun puts a halo through the spray of his flowing hair. When George

smiles, golden Palaces materialize on the hillsides of your brain. Poor

George, the forgotten Beatle, seeking asylum in our garbage air, a refugee from

Paul McCartney's declared war on his brethren.

Why is George in

New York? He really has no answer

to that question He awakens before dawn for his first full day in our town, a

victim of his accustomed London's sunrise, only six hours earlier but still

clinging to him like the last few burning words that Paul had spoken into his

ear over the telephone. The sparkle

in George's eyes blinds you to the jet fatigue on his face.

I take him a borrowed guitar and he sings me a song he has

written: ". . . Sunrise doesn't last all morning. . ."

I tell him I feel privileged to

hear it.

It

has been 18 months since George was last allowed in this country.

He was barred because of a marijuana bust of questionable notoriety.

Would they have done the same to Princess Margaret? The Beatles are another kind

of royalty and George has come just to celebrate the fact that he is permitted

to.

"I

had to pick up my visa anyway," he says.

Of

course he will spend time with Allen Klein, the Beatles? business manager, but

on this day Allen is at the funeral of his 74-year-old father.

"Allen

is the first to really take a personal interest in me," George says.

There is no bitterness when he talks of Paul.

There is only hurt.

Our first stop is at

the cigar store at 54th and Broadway to buy sunglasses. Derek Taylor, the

Beatles' press officer, is with us, talking about how unexpected Paul's attack

had been.

"He

was only supposed to write out information explaining how he made the album,?

Derek says. "Instead, he hands us this interview in which he asks himself

questions,

Outside the cigar

store, a black woman with a shaved head is arguing with a white woman who has

objected to her appearance.

'stay

out of it, wench!" the black woman shouts, walking away.

"Well,

that's New York for you," Derek says.

George

is amazed at the city's floorshow.

"Ohm

Hari Ohm," he begins chanting, like somebody crossing himself after

just seeing someone slitting someone else's throat. "Gopala Krishna. .

.Ohm Hari. . ."

At

the Underwriters? Trust Co. across the street, a teller refuses to cash one of

Derek's traveler's checks. The

guard looks at George suspiciously

"How

are you, today?? George asks him.

Ah, New York, you give with one hand and pick a pocket with the other. At every street corner, George watches the parade.

"If I saw any one of

these people in England, I'd think they were sick," he says.

"But in New York, they all look like that."

He talks about the time

he visited here before the Beatles became famous. He stayed at the Pickwick and

then took a trip to the Statue of Liberty.

Is there a city anywhere with more garbage in the streets?

George wonders where Lee Eastman, Paul's father-in-law, lives.

At Kaufman's on East 24th Street, George buys some shirts. Charles Kaufman, one of the owners, also sells him a white denim outfit, saying, "I think I've just revolutionized the music industry."

Derek

says the whiteness drains all the color out of George and hands him a bright

scarf. Kaufman stands there with a

tweedy smile.

"Just

call me Chuck," he says.

George

asks Chuck if he is related to Murray the K.

"No,?

says Chuck.

Back in the car, George brushes his long hair out of his face, pinning it behind his ears. He talks about how much Allen Klein has done for Apple Records.

the company lost

a million dollars

"I

wish he was our manager nine years ago," George says.

For its first year of Apple's existence, he says, Paul ran the company

almost single-handedly and Apple lost more than $1,000,000.

We

head down Second Avenue past the theater where Oh! Calcutta

is playing. Derek wants tickets but

doesn't know if he can cross George's puritanical streak.

John Lennon wrote one of the skits for the play, which is performed in

the nude, but George remains silent. Dylan

had asked me to get tickets to Oh! Calcutta and Bob and I had gone to see

it together. On the sidewalks, George remarks that some of the girls look very

healthy in this part of town. But still distant. Ah, New York, is this a

way to treat such an honored guest?

"Ohm Hari Ohm,"

George chants.

According to the figures

in the press, the Beatles earned a total of $17,000,000 in their first Seven years. Since

Allen Klein took over, the Beatles have earned $17,000,000 in seven months.

"How

could anyone have anything bad to say about Ringo?" George says.

I

ask him if there's a group he'd like to tour with.

"Yes,"

he says, "the Beatles."

You

can see from the way George looks up at the emerald towers that he can feast on

New York as well as anyone who comes here just to sit in the audience of the Johnny

Carson Show. As a Beatle, the

best he could do was to visit the city under house arrest. George dances down the sidewalk like a kid on a field trip

but he also knows you can't get to heaven on an express elevator.

A member of the parade? They

look at him, most of them, not even knowing who he is but because his glow tells

them he is somebody special. The

spires of the city point to vanity, but George finds God in the streets.

"Everybody's doing all the time" he says,

"and it's

Trouble?

We walk into Hudson's on Third Avenue, where they're always too busy to wait on

you if they don't feel like it. George

wants a pair of crepe-soled work shoes, but the blond-haired kid in the cellar

footwear department refuses to budge until George goes back upstairs, looks in

the window and gets the catalogue number of exactly the pair he wants.

"You

can't have me pulling out a dozen pair of shoes just to find the right one,?

the kid says.

George

hasn't been treated so rudely since the last time Paul McCartney talked to him.

Back

in the car, George laughs and wonders if he shouldn't also have bought a

baseball bat to carry into the next store he visits.

"Ohm Hari Ohm," he chants, this time

under his breath, "Gopala Krishna."

George

talks about the road he is on, knowing it must lead to God.

The Beatles? As a director of Apple, he had had to sign a letter that he

wrote with John ordering Paul not to release his McCartney album on a day

that would conflict with the release of the next Beatles record, Let It Be.

When the letter was finished, Ringo had volunteered to deliver it because he

didn't want Paul to suffer the indignity of having it handed to him by some

impersonal messenger. At Paul's

house, he gave the letter to Paul and said, "I agree with it."

Then

he had to stand there while both Paul and his wife, Linda, screamed at him.

When Ringo returned from delivering the letter, he was so drained his

face was white.

Inside

Manny's music store on West 48th Street, all the kids buying instruments

crowd around George like Little Leaguers on a visit from Mickey Mantle.

"I've

got a lot of toys for you to try out," says Henry, one of the owners, and he

breaks open a box with an electronic mixer that can make your voice sound like

horns or cellos or strings or a bassoon. George

samples a few guitars while everybody listens.

When Miriam Makeba and Stokely Carmichael walk in, Henry pulls George

over and introduces them. Miriam smiles sweetly. Stokely offers a stiff hello.

George borrows an electric guitar and a practice amp and we head

uptown for a look at Central Park. In all these years, George has yet to

set foot in the park.

'they say the best time to visit it is after 11 p.m.," George says. And he laughs.

When

we get there, we walk into the zoo, but have to turn back.

"You

can't make it?" I say.

"No,"

says George. 'the squirrels look as if they are dying, the grass seems to be

gasping for breath, the foliage is cancered. Now I know what Bob Dylan meant by

'haunted, frightened trees."?

We

walk back to the car discussing where to go for lunch.

Derek wants some place where he doesn't have to look into Anglo-Saxon

eyes. Riding in the car with

George, I could see him laughing at the city like some holy man just in from the

mountains. Where else can you witness sin in all directions only to see it

committed by clowns? Ah, George,

you were the first Beatle I ever met back there in 1964, and now look at you,

with your Indian guru's hair flowing over your shoulders like wisdom from a

fountain.

On

the dashboard radio, American troops are crossing the border into Cambodia, and

Paul's Rubicon suddenly becomes a trickle in the gutter. George listens to the

news and starts chanting his mantra, "Ohm Hari Ohm."

What

can you expect from a country that had steadfastly refused to buy his Doris Troy

record? We decide to go to the

Brasserie on East 53rd Street, where John Lennon had once had

breakfast with me, Bob Dylan and the other three Beatles. On the way, we pass a

girl in a tight jersey dress swinging her way up Lexington Avenue. She isn't

wearing a bra and we have to rush around the block for a second look.

"Tell

her I'll put her into the movies," George chuckles.

Ah,

New York, your squirrels suffer from emphysema, but you're still a garden of

humanity. We pass the braless spectacle again just in time to see a man in a

checked jacket come up from behind. Through

the open window, Derek hears the man ask her:

"Where

are you from?"

We

pull away laughing.

"Where

are you from?" Derek keeps repeating, "Where are you from?"

At the Brasserie,

George tells the waitress he's a vegetarian and she orders him a grilled filet

of sole. I ask George what he wants

to say about Paul.

"I don't want

to say anything about him, really," he answers.

At the Brasserie,

the tables are all empty except for that handful of fortunate who can afford the

leisure of sitting over lunch at 4 p.m.

"The thing

about Paul," George says, "is that apart from the personal problem of it

all, he's having a wonderful time. He's going riding and he's got horses and

he's got a farm in Scotland and he's happier with his family. And I can dig

that."

The waitress brings the filet of sole and George digs into it. He'd rather talk

When Friar Park was a nunnery, all the bare bottoms of the seraphim were painted over

about his own

house, Friar Park, which he describes as a 40-room mansion on a 36-acre estate

in Henley-on-Thames.

For 16 years it had

been a convent and someone had found it necessary to protect the nuns?

sensitivities by painting clothes on all the bare bottoms of the seraphim that

decorate it. George talked about the secret passageways and two lakes connected

by a series of grottoes and an Alpine garden and a maze you can actually get

lost in and electric light switches that have friars? faces smiling at you.

You click the friars? noses to turn on the lights.

"It

also has a thousand telephones that won't ring," George says. "It's

like a horror movie but it doesn't really have bad vibes. I've got over any of

those dark corners in the back of my mind.

It's had Christ in it for 16 years, after all."

He

orders espresso and when it arrives lie realizes he should have asked for

cappuccino. Instant Karma. It's been a long road from Liverpool's Cast Iron

Shore to saying that he still loves the Maharishi, but

George is a religious man.

"We're all just characters in the same play,

aren't we?" he says. "And

He's writing the script up there."

One of India's greatest wise men had once told

George

that success had come too cheaply for him, but now George, knows it was meant to

be that way. We lean back in our

chairs and talk about the first time we met, I, a writer for the Saturday

Evening Post, and George, just arrived from England to promote

Beatlemania. It had been on the

Beatles' second day in New York and George was alone in his room at the

Plaza, bedded down with a sore throat while the others went to Central Park to

pose for pictures and then over to the Ed Sullivan Show to rehearse for

the next night's performance. George's sister Louise had let me in to see him

and I had found him with his throat wrapped in a towel and a transistor

radio in his hands as he raised and lowered the volume of the music according to

his interest in the conversation.

As for me, all I could do was pace the floor, unable

to speak until I demanded a glass of scotch and got it.

Afterwards, George had told me he had thought I was some sort of junkie

weirdo. Now we laugh about it.

"You kept asking me 'What's bugging you?'?

George remembers. "You

wouldn't say a word until I gave you the scotch and then you kept asking, 'I

want to know what's bugging you???

Outside the sun hangs overhead mellow and

benevolent, almost enough to make New York chuckle, but then how can

concrete crack a smile and not come tumbling down?

"I thought after I moved into my new house, I'd

take a year off and do nothing," George says again, "but here I am

getting ready to make my own album in

two weeks. The point is that we're all of us

writing too much now to put it all onto one Beatles record anyway."

On

the sidewalk afterwards, someone with a mustache walks up and asks George if

he's George Harrison.

"No?

George answers and mustache walks away. "We?ve

got to explain to them that we're not these bodies," George laughs

In

the car again, we pass a group of Hari Kirshna chanters dancing down Fifth

Avenue with their shaved heads and yellow dhotis. George has already produced

two records by their London counterparts from the Radha Krishna Temple and he

now has three of them working for him at Friar Park. George jumps in his seat when he sees them.

One of the reasons he's come to New York was to find out why their

records aren't selling.

It isn't that he's sick and tired of being Beatle George. It's just that he knows he's stuck with it. Paul can have his quarter of Apple, but he'll have to leave the core. George talks about the days when the Beatles were touring and he remembers flying to Seattle in a Constellation so out of practice that they had to burn open the luggage hatch with an acetylene torch.

"Everyone

else on the tour got off, they refused to fly on it, but we---we just sat on the

floor and got wiped out," he says. "We didn't give a damn."

On

the radio, they're playing Paul's album now.

George may be the youngest of the Beatles but his attitude toward

Paul is the same as a big brother trying to wait out a kid's tantrum because the

kid can't get the candy he wants. He talks about the last time Paul spoke to

him on the phone.

"He

came on like Attila the Hun," George says.

"I had to hold the receiver away from my ear."

It

was as if the whole world was waiting for Paul's album and George was standing

in its way.

"I don't want to say

anything bad about Paul," George laughs, "but I can be egged on."

We

look for a parking space and I race another driver to get one, nearly knocking

over someone on a motorbike. George

is appalled.

"That's

New York for you," I explain. He steps out of the car, a tall, gaunt figure

that once conquered the world with the help of three partners.

"It's

great being a tourist," he says, and I suddenly remember the song he sang

to me that morning:

Darkness only stays a nighttime

In the morning it will fade away,

The daylight is good in arriving at the right time

You know it's not always gonna be this gray*

My

Pop Scene column in the New York Post had made me a star, but the

executive editor thought I was too much of a nerdy square and too stupid a

schmuck to be a star. Why? Probably because he had a relationship with my wife

that I didn't know about. After all, it was because of her entreaties to him

that he had rehired me on the Post. When she died, he figured he didn't

owe me anything any more. Besides, I had taken up with a younger, sexier woman and he

was insanely jealous. The success of my Pop Scene column had obviously bruised

his ego. In other words he did what editors have continued to do since then---he

judged me rather than judge my work.

(Photo by Arty Pomerantz)

The

night the old New York Daily Mirror folded, throwing the famous and

world-renown gossip columnist Walter Winchell out of a job---he'd been both

nationally syndicated in newspapers and featured regularly on the radio with his

familiar: "Good evening, Mr. And Mrs. America and all the ships at sea. .

."---New York Post photographer Arty Pomerantz took that picture of

a despondent Winchell and then suggested to the Post executive editor

that the Post hire Winchell.

"Listen,?

the executive editor replied, "we don't hire fading stars. We make our own

stars. And when they get to be too big for their own good, we fire them and make

someone else a star in their place."

The Post really couldn't find anyone to take my place and the POP SCENE column soon disappeared from the Post's pages. My firing was, of course, a violation of the union contract, but the executive editor boasted that he had the union in his pocket. And he did, too. He fed malicious poison about me to the rest of the staff, who, like true journalists, swallowed the poison without bothering to read the label on the bottle. He told the staff he had just discovered I was in conflict-of-interest because I was writing a column about rock music and also managing rock acts. But I had told him I was managing rock acts and would be in conflict-of-interest when I repeatedly refused his demand that I write the POP SCENE column in the first place. It was 1969 when he demanded that I write the column and I'd I'd been managing rock acts since 1964.

"Just

don't write about your own acts!" he told me. "And if you don't write

the column, I'll fire you!"

I

never wrote about my own acts but he became consumed with jealousy and, despite

the great success of my column---or else because of it---he fired me anyway. And

fixed it so I couldn't get another newspaper job in New York. Once

fired and without an income, I borrowed another $10,000 from George and tried to

make a splash bringing live country music to Manhattan.

I produced the first country music concert ever to be heard in Lincoln

Center's Philharmonic Hall. I then moved my "Country in New York? concert

series into Madison Square Garden for a few seasons longer until the shows

finally went broke. There was no audience for live country music in Manhattan.

So

while George was attaining immortality, I was sinking deeper and deeper into the

Sea of Oblivion. I needed an income so I tried to become a pot dealer.

I was such a failure as a pot dealer that I had to apply for welfare.

Meanwhile, I was growing loonier and loonier. When I was busted with

three-quarters of a gram of cocaine in my pocket, the Maryland trooper tried to

build up the case by saying I had 12 grams.

According to the law, 12 grams made me a cocaine dealer, so I became one.

I

was already a nut case. Then I started smoking freebase, the much more potent

ancestor of its better-known version, the less potent but more notorious crack.

Freebase made me see walls move and imagine I was surrounded by invisible

beings. I wasn't the only one in the arts to become trapped by cocaine.

Feebase afflicted a bunch of us in music. Before long, we were all candidates

for the funny farm. Vaguely, I remember a story I'd once heard about Ringo

quitting the basepipe after being found chasing a cat on a rooftop.

Something like that. The

first hit you took was too much! And

then every hit after that was not enough.

As

for me, the only reason I had tried drugs in the first place was so I could be a

better writer. When Pete Hamill used to tell me: "Y?gotta suffer a loss of

innocence to become a writer," I was too innocent to know what he meant. It

was Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg who got me interested in marijuana.

"Y?gotta

experience a reasoned derangement of the senses!?Allen quoted, or perhaps

misquoted, Baudelaire.

Reasoned derangement? Freebase twisted my senses into knots! I plead guilty to making the mistake of thinking that smoking freebase made me hipper. In a way, it made me hip enough to recognize how insane freebase had made my writing. Ultimately, I realized that cocaine is nothing but a goddamn lie! So I quit smoking

It

took me a few years

to get my head straight enough

to get on the Internet

freebase. In fact, I quit

smoking everything! I quit

dealing dope, vowed to live on my Social Security check and dedicated the rest

of my life to being a writer.

But

still, it took me a few years before I could get my head straight enough to see

that the Internet was the path I should take in my end run around the effectual

"blacklist? imposed on me by all my old friends in the journalism

business---friends for whom I had helped get jobs, one of whom told his brothers

I had taught him how to write. Another, now editor of a New York weekly, had

been a close enough friend to indulge in wife-swapping with me. They were all

friends who burned my bridges behind me.

And

so, although totally lacking in computer or Internet skills, I founded THE

BLACKLISTED JOURNALIST not as an e-zine but as my personal column.

After all, what a writer wants most of all is to get his writing

before the public---in other words, readers. How could I get readers when

editors refused to print me?

What

happened to my relationship with George? He

didn't desert me so much as I deserted him. I'd gone totally nuts.

I had failed in everything I'd tried. I was too embarrassed to keep

writing letters to him from Desolation Row. Our careers had taken us in opposite

directions. He'd become an

immortal and I was fast getting nowhere. Like Sisyphus, I was rolling a boulder

up a mountain only to have the boulder roll back down again.

No matter how expertly I'd roll that boulder up the mountain, it?d

always roll back down again.

Then

came Bob Dylan's anniversary concert at Madison Square Garden.

I got in touch with George. Arranged to see him. Asked would it be ok if

I taped an interview. George has never in my eyes been anything but gracious.

I saw George before the show, interviewed him on tape, brought along my

photographer son, Myles, to take pictures. I also met George's wife, Olivia

and their son, Dhani. As for Dylan, he'd ignored my request for tickets to the

concert. It was George who gave me my comps. No, I couldn't hang out backstage

like I used to. Still, I was back

in touch with George. As I said, on two of my hospitalizations, he sent flowers.

It

was when I tried to organize a memorial to Allen Ginsberg in the Central Park

Bandshell in 1998 that I invited George to attend.

Naw, he said. George was never was a big fan of Allen's. He took a

pass. The Ginsberg Memorial ended up a washout, with a bunch of poets from all

over the world reading their poetry not to a vast audience but to one another in

the Bandshell, protected from the rain.

After

my heart operation came phlebitis in my right leg. Then, on the same New

Year's Eve that George was going into the hospital after a local nut case had

stabbed him repeatedly in the chest, I was going into the hospital with a blood

clot in my left leg.

George's

injuries as a result of the stabbing apparently were worse than first reported.

He had already beaten throat cancer. Now, he faced lung cancer.

I finally wrote him a letter. Did he ever receive it?

In

July of 2001, I flew with my constant companion, Ida, to California to visit my

daughter, my grandson and my son-in-law. My grandson Noah, 8, goes to acting

camp and I had come to attend a presentation by his class.

There were three shows, one on a Thursday and two the following Sunday. I caught the first show but suddenly my right arm went numb.

I couldn't make a fist. I

couldn't control the arm.

I?d

experienced similar events through the years but they had all passed without any

lasting effects. Eventually this numbness disappeared and I was able to drive to

Pasadena the following day. It was

not until Sunday, when Noah's class was scheduled to give its final

presentation, that the numbness returned. When

I called a doctor back East, he advised me to go to a hospital emergency room.

My

daughter drove me to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Beverly Hills, where I was

placed on a gurney. A Doppler test on my neck showed that my left carotid artery

was almost completely blocked. If a

piece of that blood clot had broken off, its next stop would have been my brain.

A blood clot in my brain would have killed me or turned me into one of

those living dead, paralyzed by a massive stroke.

An

emergency operation was necessary. I lay on a bed in the corridor of the

emergency room all day until Dr. Wayne S. Gradman, one of Hollywood's

better-known vascular surgeons, cleaned the blood clot out of my carotid artery

that very night.

The

last I'd heard about George before I went under the knife was that the

tabloids reported him dying of brain cancer.

The press quoted producer Sir George Martin as saying George did not have

long to live. Was my own life so

tied to George's life? Would I ever wake up again after the surgeon slit my throat

on the operating table? When I slept, I dreamed George and I were among the

thousands running in a marathon. In

my dream, we both came out winners.

Not

only did I awaken still alive with all my faculties intact, but I also heard the

good news that George's imminent death had been nothing but a typical tabloid

exaggeration. Something like the tabloid headline that said Hillary Clinton had

run off with an alien from outer space.

I

learned that George wasn't dying of brain cancer at all.

A tabloid had misquoted Sir George Martin in an attempt to sensationalize

a false report. In other words, I

had been mistaken to think that George had cheated death at the same time I did,

after all. Still, he was under

threat from his cancer.

In

the end, we both still had more years to live.

We both had kept death at arm's length. How could I not think

that the fates had us tied together in some sort of spiritual partnership? ##

CLICK HERE TO GET TO INDEX OF COLUMN SIXTY-TWO

CLICK HERE TO GET TO INDEX

OF COLUMNS

The

Blacklisted Journalist can be contacted at P.O.Box 964, Elizabeth, NJ 07208-0964

The Blacklisted Journalist's E-Mail Address:

info@blacklistedjournalist.com

![]()

THE BLACKLISTED JOURNALIST IS A SERVICE MARK OF AL ARONOWITZ